This year was rough. I went into it thinking that it couldn’t possibly be worse than 2024, but even though what made 2024 so difficult ended positively, 2025 completely unraveled. I hit a wall. I had to make changes. And now, looking back, I’m impressed with how far I’ve come. My favorite books tell the story.

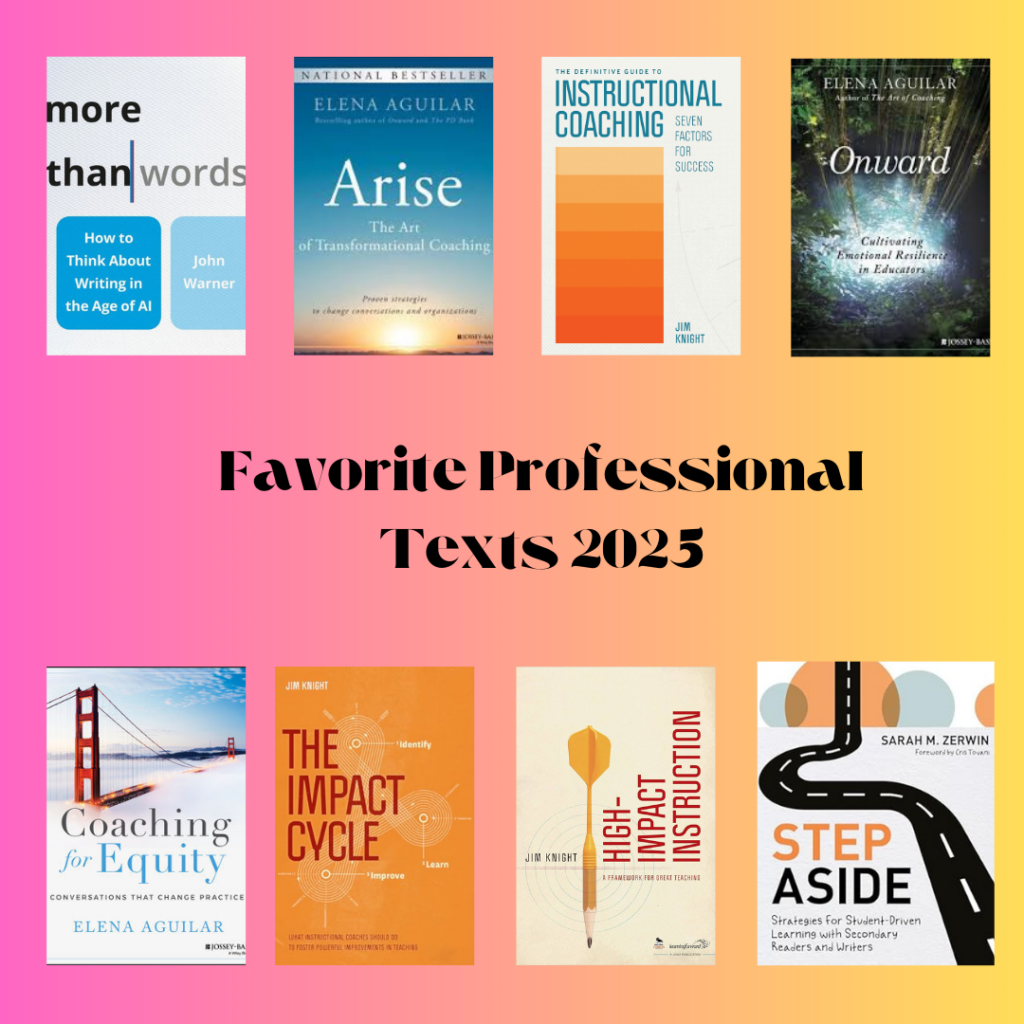

The biggest change I made was professional. By February, I knew that this would be my last year in the classroom, but I didn’t know where I could go. I knew I didn’t want to leave education, and I didn’t want to leave my school district, but I didn’t see many options. Then my district created Instructional Coaching positions. I called a former colleague who became an Instructional Coach, and she sold me on applying for the position. (I had no idea that she does consulting for Jim Knight’s Instructional Coaching Group and would eventually become our trainer.) I gave the interview process my all and was offered the position of ELA Instructional Coach! I love the job, and I adore my new colleagues, but it has been a difficult transition to say the least.

Which brings me to my fiction favorites. Most of these are rereads due to teacher book chats (Beloved), classroom teaching (The Kite Runner), and new releases (The Legendborn Cycle). In November, I decided that I needed to reread the St. Mary’s Chronicles (for the fourth time) because I was craving something familiar. This made much more sense after seeing a post online about people in middle age feeling angsty when old traditions are no longer possible and there aren’t new traditions to replace them. When I saw that, something clicked. Even though I love my new job and I have no regrets, I spent twenty-five years (almost my entire adult life) as a high school English teacher and it has completely destabilized my life. I’ve been struggling to adjust. I’ll settle in eventually, but it’s going to take some time. I need to focus on building new traditions to replace the old.

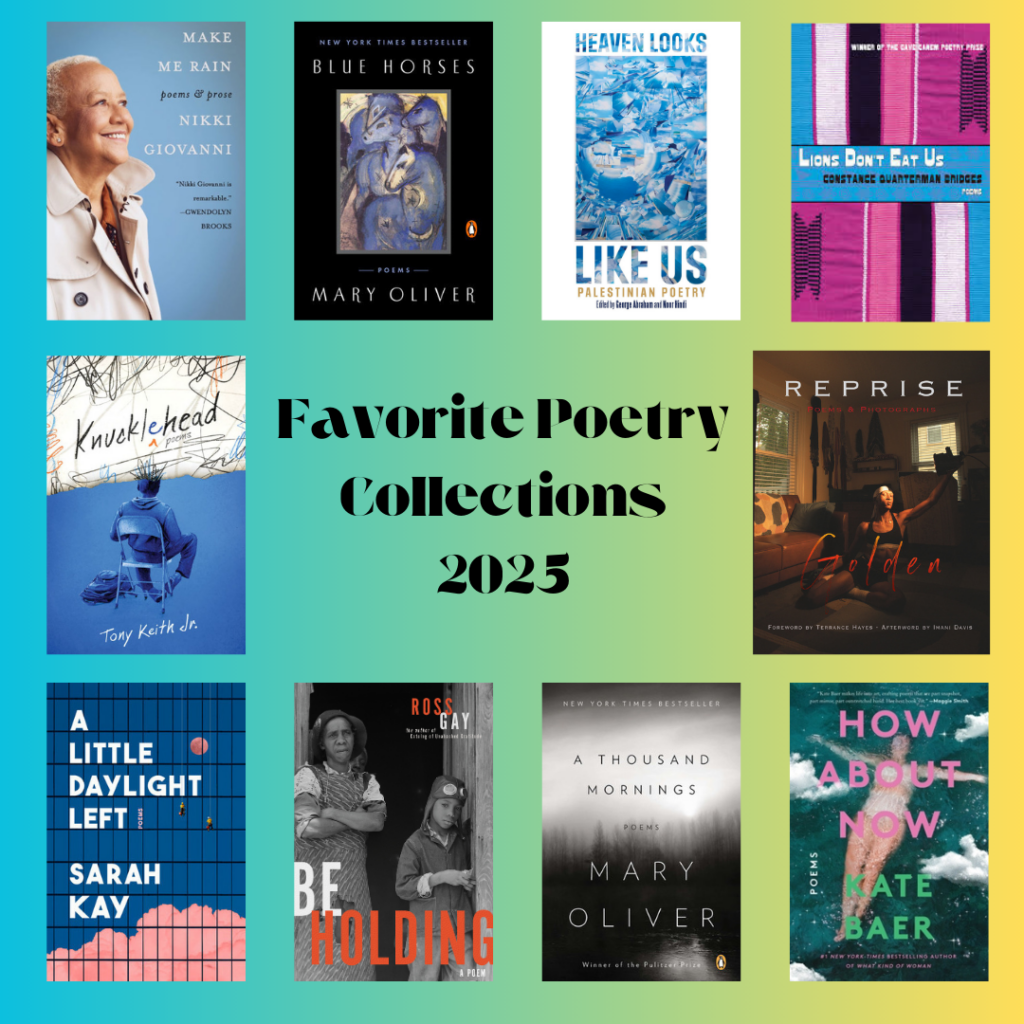

Thanks to The Sealey Challenge, I read a lot of great poetry this year. Reading Nikki Giovanni was bittersweet. She’s always been one of my favorite poets, and I don’t think I’ll ever get over her death.

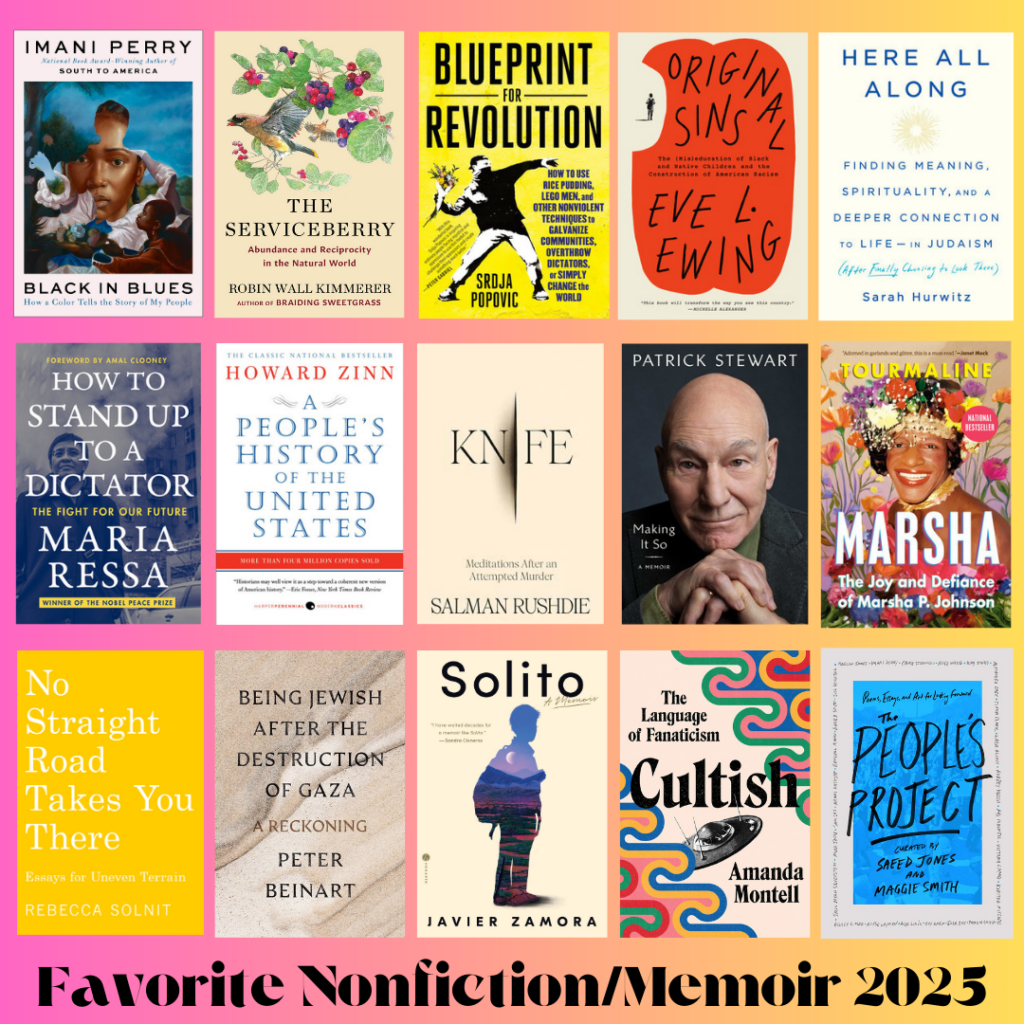

It was difficult to narrow down my nonfiction list because I gave twenty-two books five stars. Since I spent time reading about similar subjects, I selected the best from each topic.

I didn’t complete a single reading challenge, and my chapter a day plan fizzled out, but I’m not unhappy with my reading life this year. I’m learning what does and doesn’t work for me at this stage in my life, and I’ve joined some new book clubs to motivate me and push me to read out of my comfort zone. My reading plan for 2026 is to slow down, start reading through my nonfiction shelves, and not fall behind on writing reviews for the ARCs I receive.